I've been silent for a while but thought I should post something here on a conference I went to recently in Amsterdam, Holland. This conference was entitled "Reading the Present through the Past: Forms and Trajectories of Neo-Historical Fiction" and was based upon the premise of a recent collection of academic essays on historical fiction, edited by Elodie Rousselot and entitled Exoticizing the Past in Contemporary Neo-Historical Fiction (Palgrave Macmillan 2014). In this book, Rousselot argues for a type of historical fiction she terms "neo-historical", derived from the term "Neo-Victorian" (see a useful discussion of Neo-Victorianism here). Neo-historical fiction, she argues, is a type of fiction that engages with a specific historical period and tries to reconstruct it faithfully while also being very conscious of its inability to do this, thus simultaneously attempting and refusing "to render the past accurately" (Exoticizing the Past p. 4). At the same time, neo-historical fiction is "very much aimed at answering the needs and preoccupations of the present" and is persistently fascinated with "visiting - and consuming - past historical periods as a way of dealing with modern-day concerns" (p. 5). Although I'm skeptical that "neo-historical" fiction is different in this respect from what has come before (Sir Walter Scott was engaging with the past as well as writing about present-day concerns in his Waverley), it is an interesting type of classification.

The conference in question was held at the University of Amsterdam on 4 March. Rousselot herself was the first keynote speaker, and the other one was Elizabeth Wesseling, who has published widely on the historical novel, Gothic fiction, and other subjects. Aside from the two keynotes, there were many papers presented in three parallel panels during the day. These were really wide-ranging and dealt with such things as historical novels by various authors (e.g. Hilary Mantel, Eleanor Catton, Sarah Waters, A.S. Byatt), factual narratives, historiographic metafictions in Eastern Europe, American TV series (e.g. Mad Men), mashup monsters (e.g. in Penny Dreadful), murder mysteries, computer games, Brontë rewrites and adaptations, etc. As ever, my list of TBR novels and texts expanded during the day, as did my list of interesting TV series. What I found most interesting was the variety of approaches to this question of "reading the present through the past", seen for instance in Rebekah Donovan's argument on how Catton's The Luminaries engages with modern digital culture through - for instance - narrative technique, and in Ruby de Vos's analysis of how Miss Fisher's Murder Mysteries manages the representation of oppressive power structures and even rejects them from a more contemporary perspective on the level of plot and characterisation. As for myself, I gave a paper entitled "'What Gifts We Are Given': The Disruptive and Anti-Environmental Workings of Historical Violence as Presented in Susan Fletcher's Witch Light". Essentially, I argue that Fletcher portrays her central character Corrag (unjustly accused as a witch) as a child of nature, a symbol for the natural world, and that the historical event at the heart of Fletcher's novel (the 1692 Massacre of Glencoe) works to disrupt and violate the sense of natural harmony conveyed through Corrag's unique narrative perspective. As such, the message of Fletcher's novel is essentially "green"; the text is a lament for nature and how it has been exploited and destroyed by mankind, how the connection between man and nature has been severed and our life on this planet endangered as a result. These arguments on Witch Light do have to be developed further and theorized properly, and I'll continue working on it these coming months and possibly talk about it at other conferences this year.

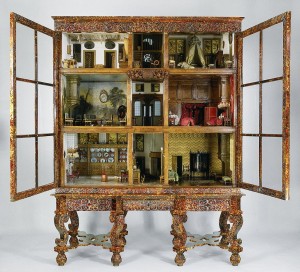

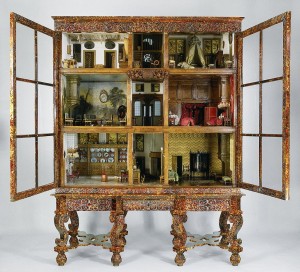

It was overall a very rewarding conference and I'm glad I went, despite suffering from a sore and inflamed knee (which meant I couldn't very well walk much around lovely Amsterdam). On the day after the conference, I visited the Rijksmuseum with a good friend of mine and saw, for instance, some paintings by Rembrandt. Also, to my delight, I came across Petronella Oortman's absolutely exquisite cabinet house, which inspired Jessie Burton's historical novel The Miniaturist, a book I enjoyed very much. Here is a picture of the cabinet house:

To finish, something slightly off topic: I found out to my delight this morning that Jackie Kay has been appointed the next Scottish Makar. This is absolutely brilliant news - she is such a good writer, one of my favourites. See news on this here. It is also wonderful because I'm including Kay's novel Trumpet in the course on Scottish 20th century fiction I'm currently teaching.