Spiny Dogfish

Squalus acanthias

1) Age determination

The spiny dogfish is a long-lived, slow growing fish. The few previous studies based on spine growth suggested a growth rate of about 3.5 cm per year, while some tagging studies suggested a slower rate of about 1.5 cm per year. Until our research had been completed, neither a method for age determination nor growth rate have been validated in the northwest Atlantic. This work has been published (Campana et al. 2006).

Samples of dogfish vertebrae and spines were collected as part of an industry/science cooperative research program which was used to determine the lifespan and growth rate of dogfish in Atlantic Canada. The goal of this work was to incorporate reliable dogfish ages into a population model so as to guide fisheries management in setting a sustainable fishing quota.

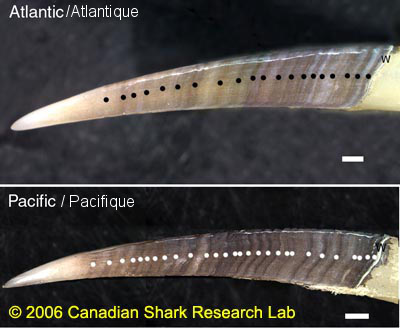

The traditional method of determining the age of dogfish has been to count the growth bands visible on the surface of their dorsal fin spines. To confirm the accuracy of the ages resulting from growth band counts, a new method of age validation was developed based on date-specific incorporation of bomb radiocarbon into spine enamel. Our results indicated that the dorsal spines of spiny dogfish recorded and preserved a bomb radiocarbon pulse in growth bands formed during the 1960s, the period during which there was extensive atmospheric testing of nuclear weapons. These results confirmed the validity of spine enamel growth band counts as accurate annual age indicators to an age of at least 45 yr. Based on the age-validated spines, the growth rate of spiny dogfish in the northwest and northeast Atlantic is substantially faster, and the longevity is substantially less, than that of dogfish in the northeast Pacific.

2) Reproduction and growth

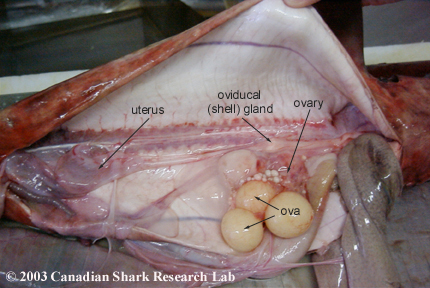

As part of an intensive study of spiny dogfish (Squalus acanthias) off the Atlantic coast of Canada, we studied the sexual maturation and growth of dogfish collected on research surveys and as part of the commercial fishery. Sexually mature and pregnant females were distributed throughout the waters of southwest Nova Scotia during the summer and fall, but moved offshore to deeper waters in the winter. Juveniles were most abundant off Georges Bank and near the edge of the Scotian Shelf during the winter. The fork length at 50% maturity for males was 55.5 cm at age 10, while that for females was 72.5 cm at age 16. Free embryos were observed in 62% of all pregnant females, with the number of embryos increasing with the size of the female. Free embryos first became apparent in June at a fork length of 16 cm, and would be expected to reach their birth size of 22-25 cm during the winter. Validated ages based on spine growth bands indicated a longevity of 31 yr. Males and females grew at similar rates until the size and age of male maturity, after which male growth rate slowed considerably. Atlantic dogfish appear to grow more quickly and die at a younger age than do northeast Pacific dogfish. Small amounts of offshore pupping in southern Nova Scotia waters probably represent the northern limits of an extended distribution centred in U.S. waters. Although they probably originate from the same population, dogfish living in the Gulf of St. Lawrence and off Newfoundland may be functionally isolated from dogfish found further south. Our results and published tagging studies suggest that both resident and migratory components of the northwest Atlantic population occupy Canadian waters. This work has been published (Campana et al. 2009b).

3) Population dynamics

Although spiny dogfish are fished commercially by Canadian fishers, the current catch quota is not scientifically based. Their high abundance in Canadian waters might make it seem that catches could be very large; however the long lifespan and slow growth rate of dogfish makes them very sensitive to overfishing. A second complication is that the spiny dogfish population in the northwest Atlantic extends from Florida in the U.S. to southern Newfoundland, with migration between Canadian and American waters. Our recent research produced a detailed population model and stock assessment which can be used as the basis for a sustainable dogfish fishery in both countries, and which properly takes into account the transboundary migration and mixing (2014 Science Advisory Report). An early review of the Canadian portion of the stock assessment is available as a 2007 Science Advisory Report and a 2007 Research Document.

4) Migration patterns of spiny dogfish

Tagging studies to date indicate that 10-20% of dogfish in Canada migrate across the Canada-U.S. border, but the frequency of migration, or even if the migration is a one-way trip, are unknown. If dogfish originate within the U.S., but migrate to Canada where they spend the rest of their lives, it may be more appropriate to manage them as a national resource rather than as a single transboundary resource.

We have two research projects underway to examine dogfish migration. Satellite tags (both PAT and X-tag) have been successfully attached to dogfish in the Bay of Fundy and the results used to track their movements in Canada and the U.S. over the course of a year. Those results are being analysed, and additional tagging is underway. A second project has surgically tagged spiny dogfish in the Bay of Fundy with acoustic transmitters in order to track their movements across acoustic receiver "fences" on the ocean bottom. This project is part of the Ocean Tracking Network (OTN).

The objectives of both tagging projects are to determine the proportion of the northwest Atlantic dogfish population which migrates across the Canada-U.S. border, the northernmost extent of any migration, and the frequency of such migrations.